Crowdfunding a Better Moustrap: First Ride on the U.S.-Built Digit Datum

August 31, 2021, Mike Ferrentino. Reprint with permission from BetaMTB

About two hours into what would turn out to be a solid four hours in the woods aboard the Digit Datum, I had a moment. Not one of THOSE moments, where the sky and ground start kaleidoscoping wildly in some yard sale of doom. No. The other kind of moment. Where instead of thinking in comparative terms, or trying to assess how well the suspension was working at speed in the roots and dust, or wondering if maybe there should be more or less anti-squat when pedaling up the steeps, I let my mind turn off and let the rest of me just ride the damn bike.

This is not always the easiest thing to do, and when faced with a single ride to try and gauge the validity of a new prototype bike that some guy is about to throw out into the world, it can be almost impossible to shut the analytic brain down. The weirder the bike is, the harder it is to find that place where you can relax the mind and ride the damn thing already. The more a given bike diverges from the accumulated database of bike behavior knowledge, the more difficult it can be to objectively hone in on where the bike performs, where it doesn’t, and more importantly, why it does or doesn’t. Fortunately for me, in this instance, it was real easy to let the Datum do its thing. It’s not very weird at all.

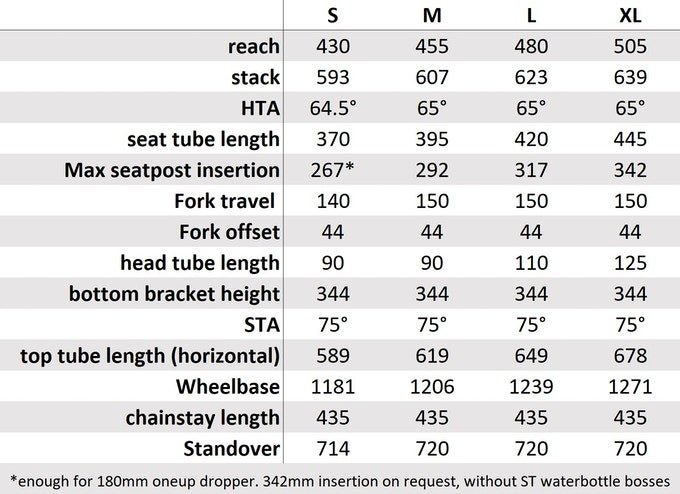

That is to say, the Digit Datum, a prototype 140mm rear/150mm front travel, 27.5”/29” trail mullet birthed from the fertile engineering mind of Tim Lane, is a very capable and predictably modern performer. If that’s all you need to know before trotting over to Tim’s Kickstarter page and plunking down your deposit, you can save yourself some eye strain and stop reading now. Good handling, thoroughly modern geo numbers, refreshingly simple suspension design, impressive chassis stiffness, and surprisingly light weight for an aluminum frame. Step right up! Click here to buy now!

Wouldn’t it be sweet if life were that simple? If our buying decisions weren’t swayed by brand allegiances, subtle but insidious marketing campaigns, and the quixotic desire to own the latest version of the perceived better mousetrap? We aren’t really wired that way, though. If we were, we’d be more easily pleased, more complacent with the status quo, and people like Tim wouldn’t be compelled to keep chipping away in search of improvement. In Tim’s case, the improvement he is seeking isn’t a radical shift in what we ride, but is more a streamlining and simplification of well-proven ideas. And the result of his quest is rendered in the form of the Datum.

So, bear in mind this is a PROTOTYPE. Things will change before this bike reaches production. For instance, that rear triangle that looks exactly like it came from a Santa Cruz Bronson will be made out of aluminum instead of carbon fiber, and won’t come from a Santa Cruz Bronson. But that front triangle? It’ll be aluminum, just like it is now, and it’ll be made in the USA. And that big long strut hiding in the top tube? It’ll still be there, operating at a low 2:1 leverage ratio, with low air pressure and massive air and oil volume. It’ll have “little red and blue knobs,” as Tim calls them, to adjust rebound and compression damping; something lacking on the prototype I rode. And the geometry will be about the same.

Tim’s impetus to found Digit (which, if successful, will give rise to a range of bikes in several different travel configurations, with the Datum sitting roughly in the “middle”) stemmed not from a dissatisfaction with the performance of current mountain bikes, but the complexity. “As an ex-mechanic, the prior-art shortcomings which most drove me to this were over-complexity and under-reliability. These are closely related – there are bikes on the market with rear suspensions that use 22 bearings and 14 pivot axles. Each offers an opportunity for mechanical lash, stripped threads, dirt ingress, misalignment, being too loose, being too tight, being f’d up from the factory, breaking, seizing, wearing, being heavy… Anyway, if you roll 22 dice, you stand a 1,100 percent higher chance of getting snake-eyes than if you only roll two.”

So, what he ended up designing is the bike you see. A concentric pivot with a short link is located at the bottom bracket. A solid rear triangle is attached to the lower link and the lower end of the shock/strut located within the top tube. The lower link pivots, the shock compresses in a linear path, and the design splits the difference in kinematic behavior between two of the more notable acronym-based systems currently on the market, while dramatically reducing the amount of hardware involved.

“I wasn’t trying to set the world on fire with novel kinematics,” says Lane. “It’s taken decades for bikes to get to a place where they aren’t severely flawed in some way or other, so I didn’t want to reinvent where evolution has driven out the gremlins. My inspiration came from looking at the industry’s two most-favored short-link 4-bar suspensions. Since they don’t like me using their acronyms, let’s call them Vanilla Praline Pecan and Dole Whip. They are pretty similar, except for the orientation of their upper links.

“At sag, on both systems, the upper-link/rear-triangle pivots move in a similar direction to the slider on my bike, and the Instant Centers are in roughly the same area. None of these things are the same, but they are analogous. Away from the sag zone, the behavior is a little different between those two systems, but given that you can’t keep pedaling while also landing a huck-to-flat, the differences become a bit more academic, not unimportant or nebulous, but not disastrous either way. So, I looked at the direction that the upper-link/rear-triangle pivot moves in the sag zone and kept everything moving in a straight line, bracketing between the away-from-sag-zone performance of the industry’s favorite frozen desserts.”

So, the long strut housed in the toptube takes the place of the upper linkage that some other designs employ, and the lower link pivots around the bottom bracket, allowing a one-piece rear triangle to do its thing. Instead of the upper link arcing, the strut acts as a slider for the upper pivot. The result is a design that eliminates at least one link, at least one pivot axle, and at least two bearings. Using the words “at least” here is doing a disservice to the simplicity of the Datum. In some comparisons, it eliminates a half a dozen or more bearings, and several axles.

The end result is an aluminum all-mountain frame and shock that will weigh under seven pounds. That shaves upwards of a pound (again, “at least”) off comparable frames of this travel and material.

Yeah, but does it work?

Yes. It works.

I didn’t get to test the “hard landing from big jumps while pedaling” behavior, because I am not that guy. And because the terrain didn’t really afford that opportunity. But I got to spin it up a solid 3,000 feet of fire road and singletrack climbing, and ripped an equal amount of dusty, rooty, ledgy descending in conditions that ranged from death-grip straight-line puckering to stall-speed root drops and up-lunges.

Geometry is right on point for the current 130-150mm-travel get-rowdy category, and the Datum is a very composed blend of stability and responsiveness. Frame stiffness and predictability was far better than I expected, given material construction and overall weight. Pedaling dynamics were really, really good. The Datum is completely indifferent to pedal inputs on fire road grinds and when punching into short steep ups, while remaining tractable and active to bump forces. Climbing composure is as good as the current best-in-show other brand contenders. Mid-speed plushness and action is also right up there. And the few times I managed to smash things going fast, there was enough progressiveness to eat it all up and remain composed and tracking straight. It’s a very good handling bike.

For a prototype bike with a hand-built prototype shock that had no external damping adjustment available, the suspension behavior was overall very good. Ride feel and responsiveness, pedaling platform and small-bump compliance was right up there with the Acronym Bikes that Tim referenced as his benchmarks. Bigger impacts—ledgy drops, smacking holes at speed, G-outs—all were dealt with competently, and the shock working in tandem with the suspension design had enough progressivity to resist bottom-out while still maintaining a plush, reactive mid-stroke.

I found myself thinking, “This is a bike I could live with.” Even though I would prefer a 29-inch rear wheel, I didn’t at any point find myself cursing the smaller hoop. Mullet fans will already be well on board with the mixed wheel sizes. The ability to simplify and remove a whole mess of pivot hardware complexity appeals to me. And being able to reduce frame weight by a pound or more over comparable aluminum bikes, with sacrificing strength or chassis rigidity? Me gusta! Especially if the ride quality and suspension performance is still there, which, in this case, it is.

But then I kept thinking about the shock. Sure, it was working fine for me, on this one ride, and sure, it’s a really cool idea. Low 2:1 leverage, massive oil capacity and similarly huge-but-tunable air volume, integrated unobtrusively into the toptube, structurally sound, easily installed and removed with a bottom bracket wrench, easily serviced with existing tools—what’s not to like? Oil should last longer before getting contaminated, lower leverage ratio means lower operating air pressures means that air spring tuning is way easier, especially for more girthy riders, streamlined design leaves room for water bottles; there’s a lot to like.

I’m kind of like the eldest oyster in The Walrus And The Carpenter in this regard. I am suspicious of new things. And I am very suspicious of suspension components that are proprietary. It has taken me a long time to come around to trunnion mount shocks, for example. I didn’t really like the look of their ears. Maybe I have had one too many big brand suspension product managers say something like “oh, no, we’ve never heard of that happening before” in response to the oil vomiting or damper rattling or air chamber burping antics of their latest “more better than anything ever” offerings. I want some assurance that I won’t be left with a dead bike if the shock suddenly belches its innards on a Saturday morning. So I queried Tim about this, and he responded with an official TLDR missive. Yes, that means “Too Long, Didn’t Read.” It also could be taken as “Tim Lane Design and Research.” He’s a funny guy, that Tim. He exudes an optimistic and unsinkable Britishness. Anyway, his reply can be read here.

As for final thoughts on the Digit Datum, would the eldest oyster buy one?

This is about the maximum travel of bike that I would contemplate buying, so bear that in mind when considering the parameters. It’s also an absolutely white hot section of the buying market these days, and there are scads of bikes out there all experimenting with different iterations of this travel/geometry layer cake. If I was shopping in terms of handling and ride quality alone, I’d buy one in a hot second. If I wanted to get a U.S.-made aluminum bike that could be built up light, the Datum potentially offers a material/weight/simplicity matrix that is hard to beat.

Personally, I would prefer 130mm rear travel and a 29-inch rear wheel, but plenty of riders would gladly take this offering instead. And if I could order a spare shock from Tim’s fancy Kickstarter page, I’d probably do that and call it good. The ride quality and simplicity appeals to me. And, even if I am suspicious about a proprietary shock, I’d still buy this in a heartbeat over a bike with an internally geared rear hub or any of this year’s high pivot idler pulley darlings. Whether or not this is your cup of tea, however, is up to you to decide. Check out Tim’s Kickstarter page for more. It’s worth a read.

Photos: Chris Wellhausen